Schwing Bioset, Inc. has been your source for complete biosolids treatment and handlings systems for over thirty years. Growing from a biosolids handling supplier, we now offer process systems as well, including nutrient management, screw press dewatering, piston pumps, screw conveyors, Class A alkaline stabilization and drying technologies, sliding frames, live bottoms, conveyors, and more. Check out this throw-back article to discover more about how a Schwing Bioset system can help solve your plant’s most challenging issues.

Alabama’s rich mining tradition—a history that dates back nearly two centuries—and the economic lift it provides (a direct and indirect value of about $5 billion, according to a recent economic census), have not been without their downside. Scars left by once highly productive strip mines dot the countryside, providing harsh contrast to the natural beauty for which the state is known. Efforts to reclaim these sites have been ongoing for some time now, but are really getting a boost of late thanks to the efforts of Jefferson County’s Village Creek WWTP. The Birmingham plant, which once simply landfilled biosolids from its operation, now converts it to a Class ‘A’ material and uses it to effect area strip mine reclamations. Aided by a pair of KSP 50 sludge pumps from Schwing Bioset (Somerset, WI) which effectively move sludge during one of the fi nal steps in the treatment process, making it ready for shipment, the result has been a win-win for all involved. Land that was once an eyesore, is once again vibrant and pristine, and a material which, in the past, was viewed as literally nothing more than a waste product, is helping making that rebirth happen.

Whole New Approach

The Village Creek WWTP is no slouch when it comes to a history of its own. First built in the early 1900s, it has undergone a series of modifications and expansions over the years, the last of which took place in 2001, essentially reshaping the face of wastewater treatment in the area, according to Terry Lane, the facility’s Plant Manager.

“To bring the plant into compliance with the federal Clean Water Act, we added another full plant to operate alongside the existing one. In addition to that, we constructed a series of 20 surge basins to aid in times of peak volume. Doing all this took the plant from a rated capacity of 60 million gallons per day (mgd) to about 420 mgd.” While the basins have a static capacity of 90 million gallons collectively, Lane says that, during those peak times (torrential rains during hurricane season is not uncommon), they can process a huge volume through the newly- configured plant.

“It only has a rated capacity of 60 mgd, but we’ve pushed 100 mgd through it with no problem. That’s allowed us to stay ahead of downpours that were associated with hurricanes Ivan, Katrina, and Rita, and that’s saying something.”

Separate But Equal

Processing of wastewater at Village Creek is fairly straightforward: sewage is first run past bar screens to remove coarse debris, then pumped into a grit removal system, then on to a primary settling tank. At that point, primary sludge is sent to anaerobic digesters then on for dewatering and biosolids treatment. The balance of the liquid stream heads for secondary aeration, additional filtering and either chlorine or UV disinfection.

“It’s important to remember that we actually have two separate plants here, both working at the same time, so when the volume of water comes in, it is split,” says Rob Brown, the facility’s maintenance supervisor. “Not surprisingly, we also have two different types of disinfection at this facility: chlorine on the old side of the plant and ultraviolet on the new side. Because both plants are active, if the chlorine treatment process should go down for some reason, the effluent can be sent here to be treated using the UV.”

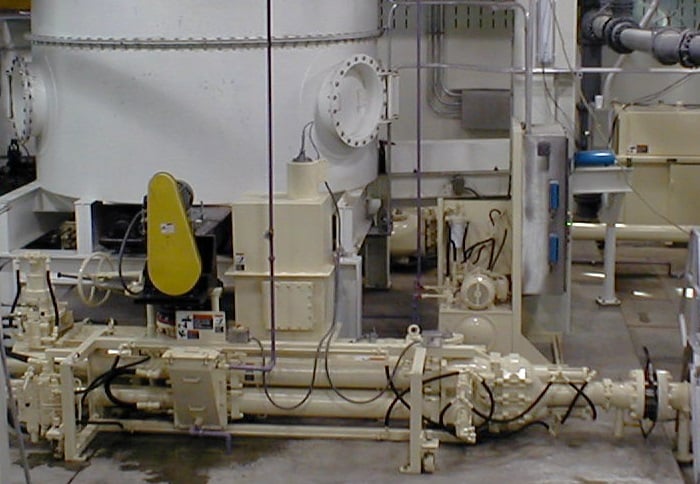

Sludge from the digesters is sent to a series of centrifuges for dewatering, then, at a dewatered rate of between 27% and 29% solids, sent via short collection screw conveyors to a Schwing Bioset 10-foot diameter, 940 ft3 sliding frame silo. “The silo serves as a metering device of sorts,” says Brown. “Using it in that way allows sludge to be more evenly fed, again via screw feeders, into the Schwing sludge pumps.”

Short Distance Runaround

The type of unit at work at Village Creek, Schwing’s KSP 50V(HD)L model, is a piston-style pump that was originally designed for use in concrete pumping projects. It is that demanding application, in fact, that initially drew plant management to select the Schwing pumps to move the dewatered sludge.

The type of unit at work at Village Creek, Schwing’s KSP 50V(HD)L model, is a piston-style pump that was originally designed for use in concrete pumping projects. It is that demanding application, in fact, that initially drew plant management to select the Schwing pumps to move the dewatered sludge.

“My boss at the time was involved in that decision,” says Terry Lane, “and his rationale was simple: he said we had some very dry solids that we had to push a fairly long way—material that would more than likely dry out even more in the lines as it moved. If a pump like that could move concrete, they felt, it could move the dewatered sludge.”

To alleviate the issue of dryness, they chose to include Schwing’s pipeline lubrication system to the pipeline. Unlike other systems that inject polymer as the lubricating medium at great expense, Schwing’s system lubricates the pipeline by simply injecting a thin fi lm of water 360 degrees around an annular groove. This system imparts pressure reductions of greater than 50% in the pipeline. “But it was the power of the pumps, more than anything, that won them over,” says Lane.

If laid in a straight line, the distance from the pumps to a pug mill—in which lime is added to the cake before transport—is relatively short: about 50 feet or so. However, that path was straight through a heavily trafficked area which would put workers at risk. To avoid that, the line was instead made to follow the contours of the building.

“By doing that we had to take it up some 20-30 feet, have it make a 90° turn, snake around and over some storage bins, then route it to the lime machine,” adds Lane. “So now we are dealing with about 150 feet of pipe rather than 50, and the power of those pumps becomes even more important.”

It’s Alive!

That final step in the process—adding lime to the biosolids—raises pH levels in order to decrease biological activity and reduce pathogen levels. Initially, Village Creek had not planned on needing alkaline stabilization. Lane says nature had other plans.

That final step in the process—adding lime to the biosolids—raises pH levels in order to decrease biological activity and reduce pathogen levels. Initially, Village Creek had not planned on needing alkaline stabilization. Lane says nature had other plans.

“The original design was intended to be completely thermophilic, which we felt would kill all the bugs, giving us the Class ‘A’ sludge we needed. At that point we hoped to store it in live-bottom hoppers, drop it directly into the trucks, and haul it out for land application at the mines. Unfortunately, we were one of several plants nationwide that began seeing fecal regrowth. When our sludge went into the thermofluid digesters, the heat was causing the bugs to encapsulate themselves. Generally, once they build that shell, they never come out again. However, after being impacted by a 2700 rpm centrifuge, many of the bugs were coming alive—and doing so in a food-rich environment, which obviously caused them to multiply. So we now add lime which kills any remaining bugs and makes the product ready for transport.”

New Lease on Life

With the biosolid stabilized, it is loaded into dump trucks and hauled to one of several local mines with which the county has contracted to do reclamation. There it is dumped and applied using specialized spreaders. The program has been in place for about ten years now and in that time Village Creek has been sending a steady stream of about a half million pounds of biosolids per week. The results, says Lane, have been impressive.

With the biosolid stabilized, it is loaded into dump trucks and hauled to one of several local mines with which the county has contracted to do reclamation. There it is dumped and applied using specialized spreaders. The program has been in place for about ten years now and in that time Village Creek has been sending a steady stream of about a half million pounds of biosolids per week. The results, says Lane, have been impressive.

“These locations have become revegetated to such a degree that we are able to grow hay at one of them and use the hay throughout our county departments,” he says. “This is a recycling program in every sense of the word. We are taking a product that was previously being sent to a landfill, finding a new use for it, growing a new product from it and using that new product—the hay—for road projects, erosion control, fill and so on. In the process we have taken a strip mine that was once a blight on the landscape, and made it a beautiful, vegetated, forested area; it is a superb application for it. And, given the number of mills and mines in this area, we can probably continue to do this for a long, long time. I’d say that’s a pretty good deal for everyone.”

Visite nuestro sitio web to read more about our products and solutions, then Contáctenos para obtener más información sobre este proyecto o descubrir cómo podemos ayudar también a su planta.