Written by Larry Trojak, Trojak Communications

Version also published in WE&T Magazine, December 2019

Springfield, Ill., wastewater treatment plant supplements its sludge disposal effort with a pair of screw presses and alkaline stabilization.

Effective wastewater treatment is predicated on equal parts science and planning. The science element of that premise includes keeping abreast of the latest technology to best manage both the treatment and disposal of biosolids. For the Sangamon County (Illinois) Water Reclamation District, that has meant rethinking its approach to biosolids, particularly in the area of dewatering prior to land application. Once solely dependent upon liquid applying its Class B byproduct, the District’s Sugar Creek Wastewater Treatment Facility recently upgraded its process to include a pair of fully-automated screw presses and a Class B alkaline stabilization system from Schwing Bioset, Inc. (Somerset, Wis.). Today, with a viable option to that liquid process in place, the plant is generating more than 17,000 lbs. of Class B cake monthly, and has peace of mind that its biosolids effort is poised for future growth.

A Pair of Plants

In addition to being the state capital, the city of Springfield (and immediate surrounding areas) hosts scores of facilities related to a booming agribusiness industry. These include one of the nation’s largest stockyards and feeder cattle facilities, as well as various creameries, meatpacking plants, flour mills, etc. To meet the demands these and other industries place on the area’s wastewater system, a pair of treatment plants were built: Spring Creek in 1928 and, to accommodate area growth, a sister plant, Sugar Creek, in 1972.

“Since that time, both plants have been retrofitted to better handle increased volumes,” said Steve Sanderfield, Sugar Creek’s plant supervisor. “Spring Creek is by far the larger of the two with an average flow of 32 mgd and a peak of 80 mgd. Here, we average 15 mgd and top out at 37.5 mgd, so our max is really only 5 million gallons more than their average. Spring Creek has been updated every couple of decades, but this plant had remained fairly constant until a 2017 upgrade which resulted in a 50% increase in both the average and peak flows. That upgrade also paved the way for the current change to the dewatering effort.”

The most recent changes were improvements for flow control and diversion to wet weather treatment facilities that included mechanically cleaned perforated plate fine screens, grit removal tanks, and activated sludge tanks designed to meet both current and future effluent phosphorus limits.

A Better Alternative

In addition to the changes mentioned above, the biosolids area also underwent a significant upgrade, including those areas for thickening, stabilization, dewatering, and storage. Until those changes were made, Sanderfield said they had only one option for disposing of the sludge created in their treatment process.

“Since the mid 1990s, to meet 40CFR Part 503 requirements for Class B Biosolids, we post-stabilized liquid sludge (1.5% TS) by adding standard hydrated lime in a slurry,” he said. “Batches of the biosolids/lime mix were held in batch mixing tanks for 24 hours, after which (if they met 503 pH requirements) they were land-applied on a 30-acre farm owned by the District. If the batch pH dropped overnight below the acceptable standard, it would have to be “re-limed” and given another 24 hours to achieve the requirements within the standards. The stabilized liquid sludge was then pumped and spray-applied through a series of fixed irrigation nozzles installed throughout the farm. Because it is a liquid-sprayed application, large sludge storage tanks are required for times when field limitations (wet seasons, frozen ground, etc.) prevent application.”

While it was less expensive to apply the stabilized sludge in liquid form, those shortcomings prompted a re-thinking. Taking a page from their sister plant’s playbook, they began looking into options for dewatering prior to land application.

“Spring Creek was already dewatering with screw presses and sending the dewatered product to a pad for drying and eventual land application,” said Sanderfield.” However, because our process differs from theirs — aerobic versus anaerobic — and we saw some shortcomings in the presses they use, we decided to look at what else was out there. Vendors were invited to show us their products and, after an impressive two-week pilot test and subsequent bid process, we chose a pair of FSP 1102 screw presses from Schwing Bioset.”

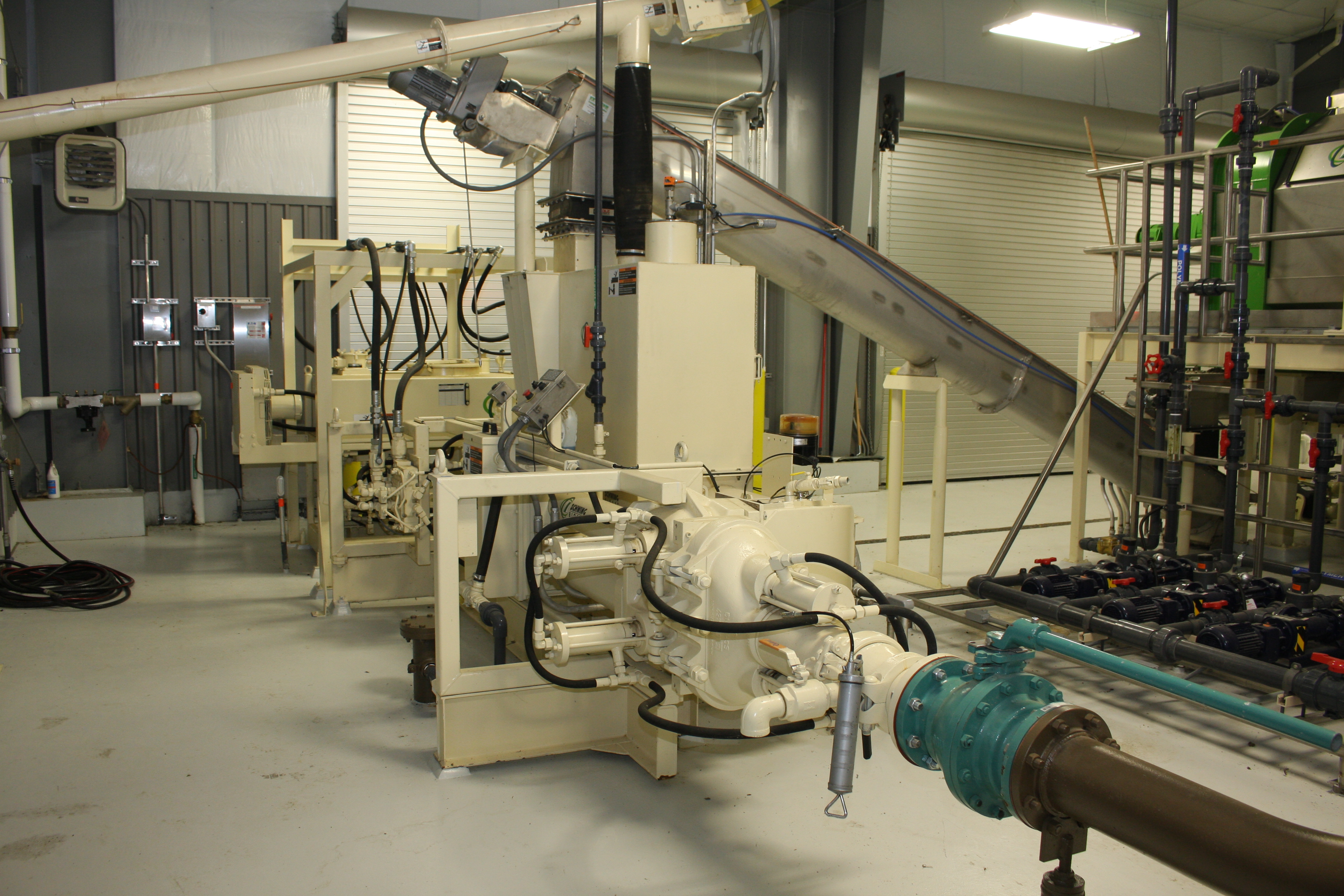

Two Are Better Than One

The model of presses in place at Sugar Creek represent one of the largest designs Schwing Bioset offers. Low speed by design, they offer dewatering results comparable to high speed centrifuges and — by nature of that slow speed and robust construction — provide a much longer lifetime of service. Sanderfield was particularly interested in one feature of the screw press: a split-screen cage that both simplifies screw removal and minimizes footprint requirements. The split cage allows the sealing lip and screen to be replaced with the screw in place — much simpler than removing the screw from one end of the machine.

“Once we knew the press would give us the product we needed, we tended to focus on the upkeep side of things,” he said. “For example: how easy would the units be to repair if one of them went down? How self-cleaning is it? What kind of wear items does it contain? That last point was important to us. The presses at Spring Creek utilize brushes that wear down and, once they do, we have to pull the entire screw out to change them. That’s a huge undertaking we wanted to avoid over here.”

Immediately after the pilot test, Sanderfield was impressed with the self-cleaning process for the Schwing Bioset presses. Unlike the units at Spring Creek which simply spray as the disc rotates and must be done when the unit is not de-watering, these utilize a low-volume, high-pressure spray ring that tracks down the length of the screw — during operation.

“This approach is so much better than others we’ve seen,” he said. “Our dewatering operation does not need to be interrupted for cleaning, and the cleaning cycle is typically only three to five minutes long, once per day. We’ve also found that after a thorough cleaning the presses can sit for a while and, when they are needed, will be in operation immediately — nothing hardens up in the lines. Because we don’t run the presses continuously here at Sugar Creek, that was important to us.”

Strength in Numbers

Although Sugar Creek never intended to run both presses at once, they nevertheless opted to go with two units rather than just one, based on equal parts the desire for redundancy and an eye toward future growth.

“For us, the purchase of the second press was definitely driven by the need for a backup,” said Sanderfield. “We are in a situation here where a press failure or, more likely, one of the pumps we have feeding each press, would be catastrophic to the process. That’s no longer a concern for us. In addition, as this area continues to grow, we are better poised to meet that growth without the need for any major overhaul.”

At Sugar Creek, sludge enters the press at roughly 1.3% solids, mixes with a polymer, and exits at 25 to 30% dry solids. While they are extremely pleased with those numbers, Sanderfield is quick to point out that, as with any press system, they have to take additional steps to deal with the filtrate. “The filtrate tends to be high in ammonia and phosphorus, so it’s considered a side stream,” he said. “When we bring that back to the plant we have to be certain to do so slowly. So when the presses run, the filtrate that is getting squeezed out is pumped back at a slow rate and is controlled by the tank level. So, if we program it to start pumping when it’s at five feet and stop when it is at three feet, that’s what it will do.”

Push of a Button

Sanderfield’s allusion to equipment autonomy is telling. Automation of the presses was also a huge consideration for Sugar Creek when making their purchase decision, and Sanderfield said they are very pleased with the level of self-operation the 1102’s can maintain.

“We start and stop it, monitor it, and run tests on the solids as it comes out,” he said. “But, for the most part, we are able to hit ‘start’ and the sludge pump will control the feed rate that we set, the presses will do their thing, the polymer will activate — it essentially runs itself and fits perfectly with the rest of the process which is also heavily

self-operating.”

From the screw press the biosolids still needed to be treated per the EPA 503 to Class B levels. The project had already started down the path to utilize another technology, but after piloting the Schwing Bioset alkaline stabilization technology with the screw press, the project switched gears. The biosolids are now routed from the screw presses to the Class B lime system (also supplied by Schwing Bioset) where quicklime is introduced to stabilize the dewatered biosolids by elevating the pH.

“As with the liquid application, according to EPA 503 we cannot field apply the material until we’ve met the 24-hour pH criteria,” said Sanderfield. “Doing so eliminates the risk of rodents, birds, animals, etc., coming in contact with the sludge and possibly transferring diseases to other animals or people. Once we’ve stabilized it in the lime system that’s no longer an issue.”

And, with an eye toward the future, Sugar Creek’s Class B lime system is also designed to facilitate expansion into a Class A Bioset alkaline stabilization process, should they choose. After treatment in the lime system, sludge — now with the consistency of a slightly wet modeling clay — is conveyed to a drying pad where it gets regularly turned using a skid-steer loader with a Brown Bear windrow turning attachment; once fully dried, it is ready for land application.

Just Gets Better

If things seem to be going great for the team at Sugar Creek, it’s because they are. They just wrapped up a well-attended open house for area residents and local officials, they are meeting all the necessary biological and phosphorus thresholds without the use of chemicals, and they were just recently nominated for Plant of the Year in Illinois.

“That last fact — a nomination for Plant of the Year — is mind-blowing, given that we’ve only been online for over a year,” said Sanderfield. “Things were crazy here for quite a while, but we are now settling in to a nice routine and the Schwing Bioset presses and alkaline system have helped provide a lot of that peace of mind. We will still do both solid and liquid land applications of the sludge — that’s always been the plan. But, since we can press in five days what would probably take us three weeks to do otherwise, the process is far more efficient than it’s ever been.”

Click here to read more about our Products, then contact us to learn more about this project or find out how we can help your plant too.

Download Our Brochures and Application Reports

Subscribe to Start Receiving Schwing Bioset eNews