Recent changes have Buffalo-area’s Bird Island WWTP poised to become a regional solution for sludge disposal.

Written by Larry Trojak, Trojak Communications

Version also published in WE&T Magazine, July 2015

Sharing the Wealth

Wastewater treatment plants, like most of their business counterparts today, are being forced to cope with a barrage of challenges including rising costs, an often-demanding customer base and an ever-changing economic landscape. To effectively deal with these and other issues, a growing number of plants are thinking outside the box to improve their operations. For the Buffalo (N.Y.) Sewer Authority (BSA), that creative effort now includes supplementing their own volume of dewatered sludge with a similar (but richer) product from neighboring communities. Doing so is allowing them to dramatically reduce incineration-related fuel costs and, at the same time, assist those communities with their sludge disposal problems. Sharing biosolids? Seems only fitting from a utility serving the “City of Good Neighbors.”

Good Day at Black Rock

First chartered in 1937 as a primary-only treatment plant, the facility now known as the Bird Island WWTP near Buffalo’s Black Rock District was expanded to include secondary treatment in the late 1970s. According to Tom Caulfield, BSA’s administrator of capital improvements and development, the expansion was in direct response to Clean Water Act mandates.

“That massive expansion — essentially, construction of a totally new secondary treatment facility — added aeration and secondary clarification capabilities,” he says. “Even today, few people realize that Bird Island is the second largest wastewater treatment plant in all of New York state. Only the Newtown Creek WWTP in Brooklyn’s Greenpoint community is larger. We are designed to handle a peak flow of up to 540 million gallons per day (MGD) but are currently averaging flows of about 130 mgd.”

In addition to the city of Buffalo, Bird Island WWTP serves a good number of other neighboring communities including the villages of Sloan and Depew, and the towns of West Seneca, Orchard Park, Alden, Lancaster, Cheektowaga, Elma and includes a limited amount of flow from the Town of Tonawanda. Despite that vast coverage, it was actually the nearby Town of Amherst which, by choosing to re-think its overall approach to sludge disposal, dramatically changed the complexion of Bird Island WWTP’s biosolids processing operation.

Plan B for Amherst

For more than a decade, the Town of Amherst had been dewatering its sludge, pelletizing it, and working hard to generate a market for it as a high-grade fertilizer product. In 2010, however, rising operational costs, coupled with aging equipment, prompted them to rethink that strategy, according to Michael Letina, BSA’s treatment plant superintendent.

“Amherst was hoping to have the same level of success with their fertilizer pellet that the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District has had with their Milorganite, but that just never happened,” he says. “Then they reached a point at which their digesters needed serious repair and, rather than incur the costs of upgrading the system, they started looking for alternatives. They determined that sending their [dewatered] waste activated sludge (WAS) here would make the most sense for them both logistically and financially.”

In early 2010 a 10-year agreement was signed, approving Amherst’s shipment of material from their facility to Bird Island. Today, about 70,000 pounds of WAS is trucked in on a daily basis from Amherst to the Black Rock location.

To Burn or Not to Burn

Getting Bird Island to a point where they could efficiently accept Amherst’s sludge was no small undertaking. Working through the Buffalo branch of the engineering firm Arcadis U.S., Inc., plans were drawn up and considered, with the final $2.38 million construction contract offering a couple of options for the material being delivered.

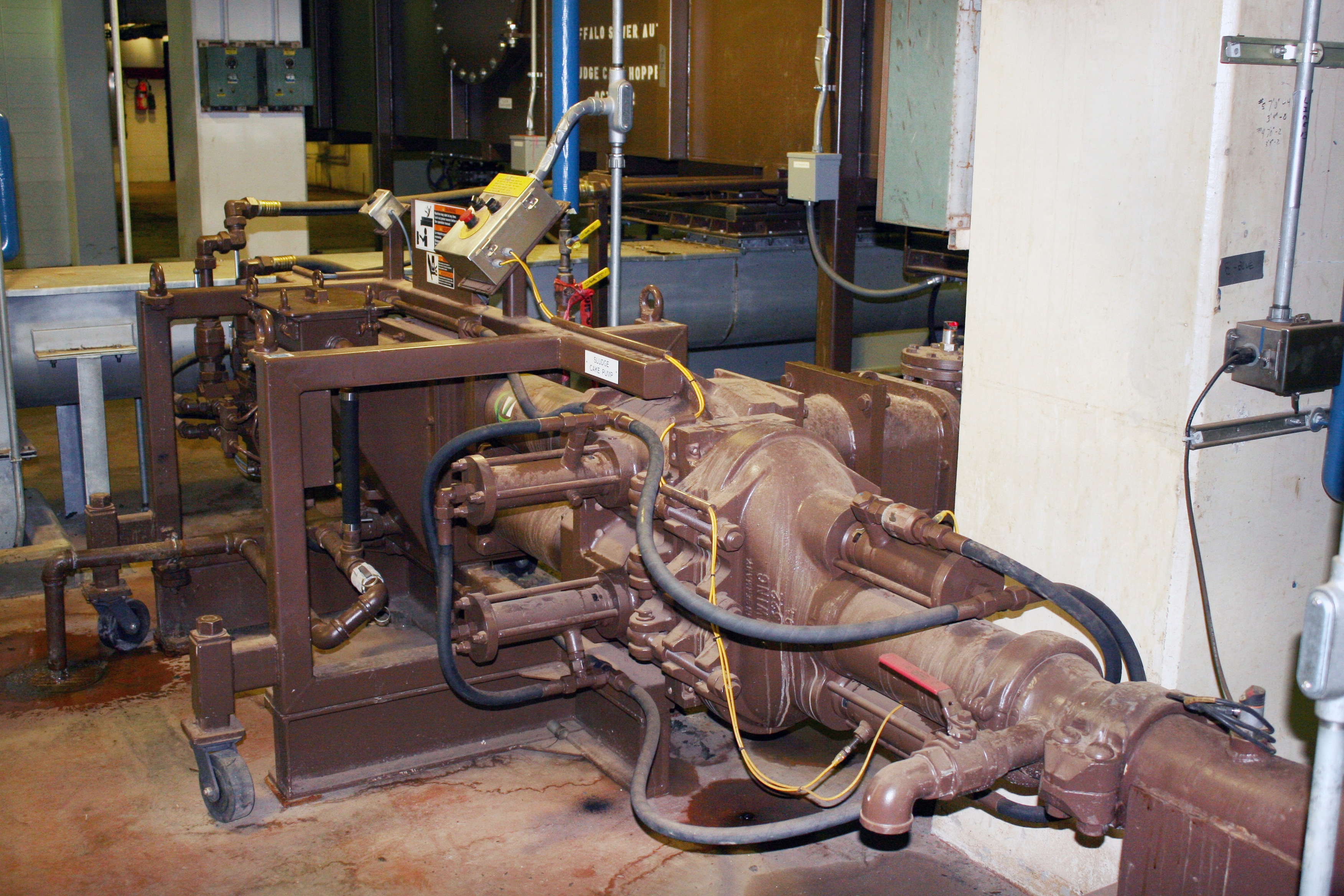

“Essentially, the process began with construction crews cutting a hole in the15-inch thick floor of our truck weighing area, and installing a 60 cubic yard push floor bin supplied by Schwing Bioset (Somerset, WI). There, customers’ vehicles — at the beginning it was only the Town of Amherst’s trucks — could empty the dewatered WAS they were delivering,” says Letina. “The hopper contains a hydraulic push-floor that sends material through a gate where it drops into a screw feeder, then into a Schwing Bioset KSP 12V (HD) pump designed for 1,000 psi operating pressure which pushes it up to the third floor for incineration. Depending on our needs at the time, we also have the option to take that sludge out of the bin through an alternate extraction screw conveyor and drop it down to the sub basement where it can be re-wetted and sent to our digesters to produce methane.”

Adding Amherst’s dewatered WAS to the operation was a win-win in a number of regards. Not only did it address the town’s needs to effectively dispose of its sludge, the material’s high volatile content — generally in the 76% range — proved an excellent fuel for Bird Island’s incineration effort.

“Our own biosolids are anaerobically digested and, as a result, are only about 46 percent volatile, so it takes a considerable amount of gas to burn,” says Letina. “However, putting material from Amherst on top of it is like throwing lighter fluid on an open flame. Now, we continually monitor to see whether methane production or incineration will serve us better. It’s a nice luxury to have.”

On the Up and Up

With the Amherst-generated cake added to the equation, steady, reliable equipment operation is key to ensuring that both plants realize the maximum benefit of the new effort. The Schwing Bioset biosolids pump installed as part of the recent expansion has definitely risen to the challenge, says Alex Emmerson, BSA’s process coordinator.

“The pump has its work cut out for it, taking material that is generally in the 26% to 28% solids range and sending it more than 65 feet straight up to the conveyor feeding the incinerator,” he says. “To handle issues of excessive in-line friction, Schwing Bioset also supplied an injection-ring system that lubricates the pipe wall with a small amount of fluid as it moves.”

On average, Bird Island maintains about 900,000 pounds of inventory on its secondary treatment system. They recently had a case, however, in which inventories ran low, prompting the need to curtail wasting. “That meant we had to rely solely on the ‘outside’ Biosolids and really push the pump — sometimes operating it at three times its normal speed,” says Emmerson. “Even with the added workload we were consistently pumping 8,000 pounds per hour and never had an issue. It’s definitely a key part of the operation.”

He adds that there is a certain peace of mind in knowing that the outside biosolids operation (which just recently was expanded to include a similar agreement with the Town of Tonawanda), affords them a nice contingency plan.

“Now we know we are covered if something unforeseen — like a centrifuge failure — occurs and we need to step up production using the imported biosolids to meet incinerator demand.”

Money in the Bank

BSA has been prepping for growth for some time now, an effort that included a recent incinerator rehab. According to Letina, that updating, which included a new scrubber pack and burners, and carried a price tag of nearly $5 million, allows them to meet new environmental regulations that take effect in March, 2016. However, their ability to become a regional biosolids processor — and keep costs steady in doing so — is a real source of pride.

“Much of the preliminary work for this part of the operation is the brainchild of Jim Keller our treatment plant superintendent and Roberta ‘Robbie’ Gaiek, BSA’s plant administrator,” says Caulfield. “Because of their planning and foresight, we are already seeing the fruits of this effort. Before the installation of the centrifuges and digesters, this plant used about 550,000 decatherms (Dth) of natural gas a year; now we are averaging about 175,000. So we’ve effectively cut our gas consumption by about 65%. With the rehabbed incinerator and addition of the higher volatile material from Amherst and Tonawanda, even with the added volumes we hope to be down around 150,000 to 160,000 Dth a year.”

The savings realized from Bird Island’s reduction in fuel costs is being reinvested in onsite projects, eliminating the need for bonding and the headaches that come with it. “More importantly,” says Caulfield, “it has also allowed us to go nine years now without a rate hike to our customers. In light of what the economy has been through, not a lot of utilities can say that.”

Looking Forward

Future plans under consideration —with additional anticipated savings — include a heat and power project designed to recover and re-use exhaust from the plant’s incinerators.

“The original plan was designed to incorporate the use of three waste/heat recovery boilers, says Letina. “Once operational, the exhaust off the afterburners would create steam which would power a turbine and generate 1.5 – 2 megawatts of electricity — about 1/3 of our current load. Our electric bill right now is substantial — about $4.5 – $5 million a year. If we can save another $1.5 to $2 million annually, that money can be reinvested into the infrastructure, again avoiding bonding and rate hikes. The last few years have been challenging but definitely worth the effort. With these proposed changes and our growing role as a regional biosolids processor, this is an exciting time for Bird Island and BSA overall.”

To learn more about Schwing Bioset, our products and engineering, or this project specifically, please call 715-247-3433, email marketing@schwingbioset.com, view our website, or find us on social media.

To view a version of this story published in WE&T Magazine, click here.

Download Our Brochures and Application Reports

Subscribe to Start Receiving Schwing Bioset eNews